Evidence-Based Recommendations on the Use of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Monoclonal Antibodies (Casirivimab + Imdevimab, and Sotrovimab) for Adults in Ontario

Authors:Jacob J. Bailey, Andrew M. Morris, Sally Bean, Eyal Cohen, Jonathan Gubbay, Yona Lunsky, Samir Patel, Vanessa Tran, Katherine J. Miller, Zainab Abdurrahman, Stephanie Carlin, William Ciccotelli, Jennifer Gibson, Jennie Johnstone, Tiffany Kan, Bradley Langford, Elizabeth Leung, Ullanda Neil, Sumit Raybardan, Janet Smylie, Anupma Wadhwa, Peter Jüni, Menaka Pai, on behalf of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table and the Drugs & Biologics Clinical Practice Guidelines Working Group

Key Message

Critically and Moderately Ill Patients

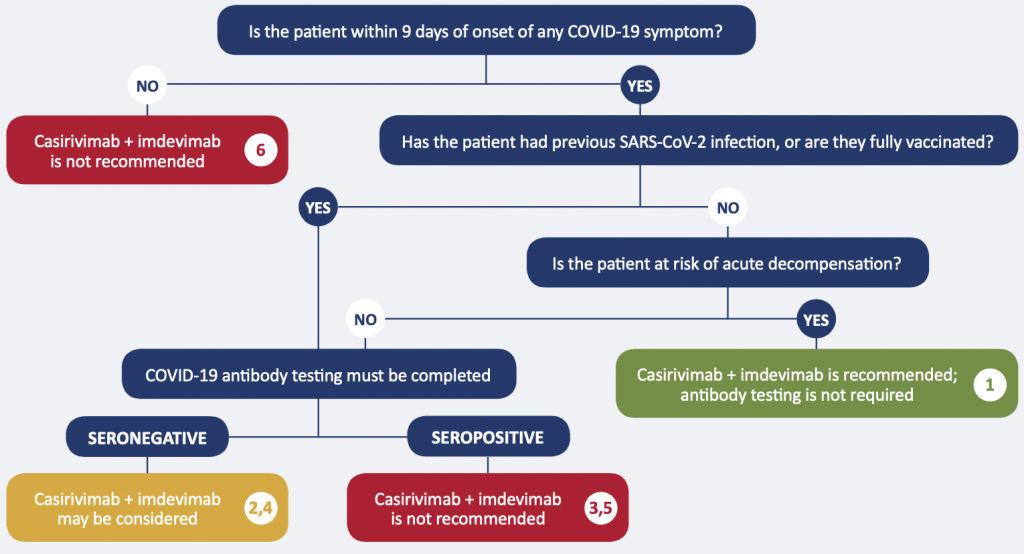

In clinically unstable patients with no history of COVID-19 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 2400 mg intravenous (IV) is recommended if patients are within 9 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom AND have demonstrated rapid clinical deterioration. Antibody testing is not required in this case.

In clinically stable patients with or without a history of COVID-19 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 2400 mg IV may be considered if patients are within 9 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom AND are not at risk of acute decompensation AND if COVID-19 anti-spike antibody testing demonstrates that they are seronegative. Casirivimab + imdevimab is not recommended for moderately/critically ill patients who are beyond 9 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom, whether or not they are presumed to have immunity to SARS-CoV-2.

Mildly Ill Patients

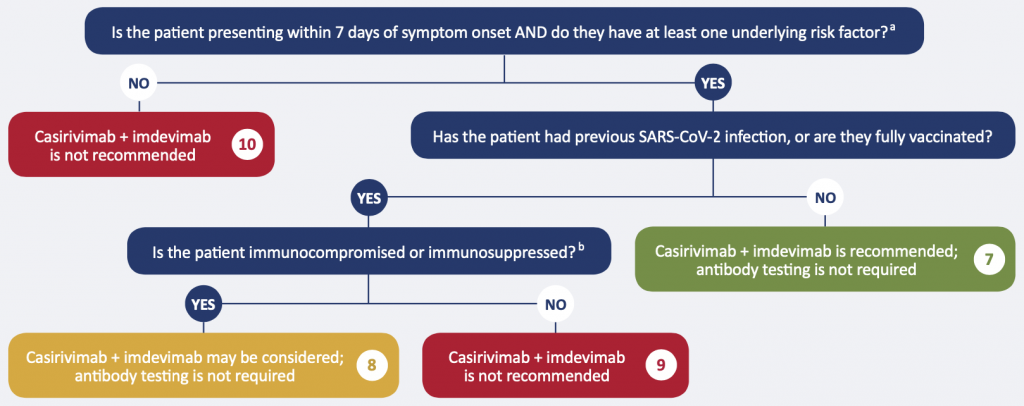

Antibody testing is not required in mildly ill patients. In patients with no history of COVID-19 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 1200 mg IV or subcutaneous (SC) OR sotrovimab at a dose of 500 mg IV is recommended if patients have confirmed, symptomatic COVID-19 AND are within 7 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom AND have at least one of the following risk factors: age > 50, indigenous (First Nations, Inuit, or Metis), obesity, cardiovascular disease (including hypertension), chronic lung disease (including asthma), chronic metabolic disease (including diabetes), chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, immunosuppression, or receipt of immunosuppressants.

In patients with a history of COVID-19 infection or who have received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 1200 mg IV or SC OR sotrovimab at a dose of 500 mg IV may be considered if patients have confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 AND are within 7 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom AND are immunocompromised or are taking immunosuppressant medications. In patients with a history of COVID-19 infection or who have received a full recommended schedule of vaccination with risk factors other than immunocompromise or immunosuppression, anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies (AmAbs) are not recommended as these patients have presumed immunity. In patients with no risk factors, AmAbs are not recommended as these patients are at low risk of adverse outcomes.

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

Casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 1200 mg IV or SC OR sotrovimab at a dose of 500 mg IV is recommended for unvaccinated individuals who are currently hospital in-patients or residing in congregate settings (e.g., long-term care settings, retirement homes, shelters, correctional facilities) who have had a high-risk exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (as determined by an expert in Infection Prevention and Control or Public Health) and who are at high-risk to progress to moderate or severe COVID-19. Determination of using an AmAb for post-exposure prophylaxis should take into account the nature and context of their exposure.

Implementation Considerations

It is recommended that AmAb therapy be administered to non-hospitalized individuals across Ontario using a hybrid network that includes – but is not limited to – mobile integrated healthcare (MIH) services, community paramedicine (CP), and outpatient infusion clinics. Experience from other jurisdictions suggests that hybrid administration approaches coupled with substantial health care system coordination are required to deliver AmAbs in a timely and equitable fashion to those who are likely to benefit from them.

Ontario’s supply of AmAbs is limited, and demand by eligible patients may exceed supply in the near future. Understanding the impact of these agents on patient- and system-important outcomes will ensure that they are used equitably and to greatest benefit.

There are clear barriers to allocating AmAbs ethically and equitably. A number of strategies are suggested to address these barriers, including optimization of dosing, distribution, supply, administration, allocation, dashboarding, and application of an evidence-informed risk framework for patient selection.

Lay Summary

When viruses infect you, your body mounts an immune response that includes the creation of protective molecules called antibodies. Antibodies can recognize very specific targets, such as specific proteins on the surface of a virus. People with antibodies to a virus can neutralize that same virus by recognizing it, attaching to it, and preventing it from spreading throughout the body and causing an infection.

How Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Monoclonal Antibodies (AmAbs) Work

One of the proteins on the surface of the SARS-CoV-2 virus – the organism that causes COVID-19 – is the spike protein. Currently available SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies (also called “anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies” or “AmAbs”) do not come from humans. They are made in the lab and work the same way as the antibodies people can develop following an infection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus or vaccination. Casirivimab + imdevimab (a mixture of two different antibodies) and sotrovimab are examples of anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies. They can neutralize the SARS-CoV-2 virus by recognizing it, attaching to it, and preventing it from spreading through the body. These monoclonal antibodies are licensed for use in Canada.

How We Came to Our Recommendations

There are a variety of randomized clinical trials evaluating different AmAbs in different COVID-19 patients: from people who don’t have symptoms but had a high-risk exposure to someone infected with COVID-19, to mild illness in people still being cared for at home, to people with more severe illness who need to be in the hospital. These trials were conducted at different stages of the pandemic, with different virus variants circulating. Some of the studies took place early in the pandemic, where doctors and nurses didn’t have many other drugs to treat COVID-19. We took all of this into consideration. We also considered that Canada does not have a large supply of AmAbs right now. We believe most Canadians want to use medications that will help them in important ways, like preventing them from getting seriously ill with COVID-19, ending up in the hospital, or dying. We also believe most Canadians think about how treatments for COVID-19 might reduce the burden on our health care system, to ensure as many people as possible get good care – whether they have COVID-19 or not.

Our Recommendations for Moderately and Severely Ill Patients Who are Sick Enough to be in Hospital

If you are within 9 days of starting to have any symptom of COVID-19, you may benefit from casirivimab + imdevimab. If you have never had COVID-19, are not fully vaccinated (i.e., have received the full recommended schedule of doses of Vaxzevria, Comirnaty, and/or Spikevax), and a doctor feels you are rapidly getting sicker, you should get casirivimab + imdevimab 2400 mg IV. You do not need a test to see if you already have your own anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

If you have never had COVID-19 and are not fully vaccinated (i.e., have received the full recommended schedule of doses of Vaxzevria, Comirnaty, and/or Spikevax), but your medical condition is stable, you may get casirivimab + imdevimab 2400 mg IV – but only if an antibody test shows you do not already have your own antibodies. If you do have your own anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, you should not get anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies.

If you have had COVID-19 and/or are fully vaccinated (i.e., have received the full recommended schedule of doses of Vaxzevria, Comirnaty, and/or Spikevax) but your medical condition is stable, you may get casirivimab + imdevimab 2400 mg IV – but only if an antibody test shows you do not already have your own anti-spike antibodies. If you have your own anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, you should not get anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies.

Our Recommendations for Mildly Ill Patients Who are Sick, but Still Well Enough to be Cared for Outside of Hospital

At this time, we recommend that Ontarians receive casirivimab + imdevimab or sotrovimab. Casirivimab + imdevimab may be more convenient to use since it can be given either as an infusion into the veins or as an injection under the skin, while sotrovimab can only be given intravenously.

If you are within 7 days of starting to have any symptom of COVID-19, you may benefit from casirivimab + imdevimab or sotrovimab in certain circumstances as described below. If your symptoms started more than 7 days ago, you should not get it.

People with COVID-19 who are still well enough to be cared for outside of the hospital do not need to be tested to see if they have their own antibodies if they are being considered for treatment with anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies. They do need to have symptoms of COVID-19, and their infection needs to be confirmed with an appropriate lab test.

If you have never had COVID-19 and are not fully vaccinated (i.e., you have not received the full recommended schedule of doses of Vaxzevria, Comirnaty, and/or Spikevax) and have at least one underlying risk factor, you should get casirivimab + imdevimab 1200 mg IV or SC, or sotrovimab 500 mg IV.

If you have had COVID-19 and/or are fully vaccinated (i.e., you have received the full recommended schedule of doses of Vaxzevria, Comirnaty, and/or Spikevax) and you are immunocompromised or immunosuppressed, you may get casirivimab + imdevimab 1200 mg IV or SC, or sotrovimab 500 mg IV.

If you have had COVID-19 and/or are fully vaccinated (i.e., you have received the full recommended schedule of doses of Vaxzevria, Comirnaty, and/or Spikevax) and you have no underlying risk factors (including no immunocompromise or immunosuppression), you should not get anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibodies.

If you currently a hospital in-patient or live in a congregate setting such as long-term care, a retirement home, a group home, a shelter, or correctional facility, have had a high-risk exposure to SARS-CoV-2, and are at high-risk to progress to moderate or severe COVID-19, then you should be considered for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), considering the nature and extent of your exposure. Casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 1200 mg IV or SC or sotrovimab at a dose of 500 mg IV is recommended for such patients.

Summary

Background

The SARS-CoV-2 spike protein is involved in receptor recognition, viral attachment, and entry into host cells.1 AmAbs work by binding non-competitively to the important domains of the virus (e.g., the critical receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein), thereby stopping the virus from binding to and/or entering human cells. Passive immunization with AmAbs appears to prevent disease progression in recently diagnosed COVID-19 patients.

Currently, there are three AmAbs authorized by interim order from Health Canada: bamlanivimab (LY-CoV-555), casirivimab + imdevimab (marketed in the European Union and United Kingdom as Ronapreve, and as REGEN-COV in the United States), and sotrovimab (Sotrovimab). Bamlanivimab monotherapy is no longer recommended for use in COVID-19, due to inadequate neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern; the combination of bamlanivimab and etesevimab is not currently approved for use in Canada. This brief will address the use of casirivimab (cas-ih-RIH-vih-mab) + imdevimab (IM-DEH-vih-mab), and sotrovimab (so-TROE-vih-mab); these recombinant human monoclonal antibodies bind to distinct but overlapping regions on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein thereby preventing viral entry into cells, and will be referred to throughout the document as AmAbs.

Health Canada has recently approved these products for treatment of COVID-19 in mild to moderately ill non-hospitalized patients who are at a high risk for progression to hospitalization and/or death.

Casirivimab + imdevimab is approved as a single IV infusion of 2400 mg (1200 mg of each monoclonal antibody component) over a minimum of 60 minutes, with monitoring for at least 60 minutes after infusion. Sotrovimab is approved as a single IV infusion of 500 mg over 60 minutes, with monitoring for 60 minutes after infusion. Casirivimab + imdevimab has been used at doses of 8000 mg IV (4000 mg of each monoclonal antibody component) and 2400 mg IV in hospitalized patients,2,3 and has been administered subcutaneously at a dose of 1200 mg (600 mg of each monoclonal antibody component) in asymptomatic household contacts of COVID-19.4

The demand for AmAbs may be high in the current and future waves of the pandemic; individuals who do not have existing immunity (either because they are unvaccinated, or because they are immunocompromised/immunosuppressed and cannot mount an adequate immune response to vaccination) are at the highest risk of serious outcomes. Demand for AmAbs will therefore correlate with case counts of non-immune individuals.

There are federal, provincial, and territorial frameworks to manage drug shortages in Canada, enhanced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, frameworks exist to manage drug allocation. However, increasing numbers of patients with COVID-19 eligible for treatment with AmAbs may pose a challenge for the allocation and distribution of medications that are costly and in limited supply, due to a high demand worldwide.

Questions

What is the evidence to support use of AmAbs in patients with moderate/severe COVID-19?

What is the evidence to support use of AmAbs in patients with mild COVID-19?

What is the evidence to support use of AmAbs in post-exposure prophylaxis settings?

What clinical recommendations has the Clinical Practice Guidelines Working Group (CPG WG) made around the use of AmAbs in symptomatic COVID-19?

Are there special considerations with pregnancy and lactation?

What factors must be considered to promote ethical and equitable allocation of AmAbs?

How can we optimize the distribution, supply, and administration of AmAbs to maximize benefit?

Findings

What Is the Evidence to Support Use of AmAbs in Patients with Moderate/Severe COVID-19?

The RECOVERY trial investigated the effect of casirivimab + imdevimab in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.2 It randomized patients to one of three arms: usual care and convalescent plasma; usual care and casirivimab + imdevimab; or usual care alone. The convalescent plasma arm was stopped early for lack of benefit. The results of the casirivimab + imdevimab arm of RECOVERY have been published as a preprint.3

Eligible patients had clinically suspected or lab confirmed COVID-19, were over age 12, weighed over 40 kg, and in the judgement of the treating clinician, did not have a contraindication to casirivimab + imdevimab. Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination did not affect eligibility. Pregnant and breastfeeding people were eligible for randomization. Between September 2020 and May 2021, 9785 hospitalized patients at 127 sites in the UK randomized to the casirivimab + imdevimab arm received a single 8000 mg IV infusion (4000 mg casirivimab/4000 mg imdevimab) infused over 60 +/- 15 minutes.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the usual care and the usual care plus casirivimab + imdevimab groups. At randomization, 62% of the patients required oxygen therapy, 26% required non-invasive ventilation (with 6% progressing to invasive ventilation), and 7% required no oxygen therapy. Nearly all patients enrolled in the trial received steroids (94%). Fewer received remdesivir (25%) and tocilizumab (14%). Baseline antibody testing revealed 54% of patients had baseline SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (seropositive patients) and 32% were antibody negative (seronegative patients), with 14% missing antibody data. However, baseline antibody testing was not used for stratification of randomization. The median time from symptom onset was 9 days for all patients (interquartile range 6 to 12 days), and 7 days for seronegative patients (interquartile range 6 to 10 days).

Among all patients in the trial there was no difference in death at 28 days, discharge alive from hospital, and progression to invasive mechanical ventilation or death. There was no significant harm signal, including infusion-related adverse events.

Among seronegative patients, casirivimab + imdevimab was associated with reduced mortality at 28 days compared to usual care (24% in casirivimab + imdevimab vs 30% in usual care, RR 0.80 confidence interval (CI) 0.70-0.91, p-value = 0.001), increased probability of discharge alive from hospital (64% vs 58%, RR 1.19 CI 1.08-1.30, p < 0.001), and reduced progression to invasive mechanical ventilation or death (30% vs 37%, RR 0.83 CI 0.75-0.82, p < 0.001). Casirivimab + imdevimab conferred an absolute risk reduction of 6 fewer deaths at 28 days for 100 patients treated.

Among seropositive patients, there was no difference in nearly all of these outcomes and those with unknown antibody status. However, there was a trend to increased mortality at 28 days in patients who were seropositive and received casirivimab + imdevimab (16% vs 15%, RR 1.09 CI 0.95-1.26). Due to the time window of enrollment, it is likely that most enrolled patients in the casirivimab + imdevimab arms of RECOVERY were not infected with the Delta variant.

A second trial, the Covid-19 Phase 2/3 Hospitalized Trial, is part of an adaptive, industry-sponsored, phase 1/2/3 trial for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 and a range of disease severities. This trial included patients with mild and moderate severity illness, and randomized patients on no or supplemental low-flow oxygen to one of three arms: intravenous casirivimab + imdevimab at doses of 2400 mg or 8000 mg, or placebo in a 1:1:1 allocation. The results of this phase of the trial have been published as a preprint.

Eligible patients had clinically suspected or lab confirmed COVID-19, ≤72 hours with symptom onset ≤10 days from randomization, were over age 18, and in the judgement of the treating clinician, did not have a contraindication to casirivimab + imdevimab. Patients needed to maintain an oxygen saturation >93% on room air or low-flow oxygen via nasal cannula, simple face mask, or other similar device. Previous SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination did not affect eligibility. Pregnant and breastfeeding people were excluded. All patients were assessed for baseline viral load and the presence or absence of the following anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: anti-spike IgA, anti-spike IgG, and anti-nucleocapsid IgG.

The primary virologic efficacy endpoint was the time-weighted average daily change from baseline viral load in nasopharyngeal samples through day 7. The primary clinical efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients who died or required mechanical ventilation from day 6-29 and day 1-29. Secondary efficacy endpoints included all-cause mortality and discharge from/readmission to hospital. Between June 10 2020 and April 9 2021, 1364 hospitalized patients at 103 sites in the United States, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Moldova, and Romania were randomized to a single IV infusion of casirivimab + imdevimab arm 8000 mg, 2400 mg, or placebo IV infusion over 60 +/- 15 minutes. The trial was discontinued prematurely due to low recruitment, ascribed partially to the publication of the RECOVERY Trial’s AmAbs results.

Baseline characteristics were generally similar between the usual care and the usual care plus casirivimab + imdevimab groups, although there was a higher proportion of seropositive patients in the placebo group (51%) compared to the casirivimab + imdevimab combined arms (46%). At randomization, 56% of the patients required low-flow oxygen therapy. A majority of patients in the trial received steroids (75%), and remdesivir (55%); tocilizumab use is unreported. Baseline antibody testing revealed 43% of patients had baseline SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (seropositive patients) and 48% were antibody negative (seronegative patients), with 14% missing antibody data. However, baseline antibody testing was not used for stratification of randomization. The median time from symptom onset was 6 days for all patients (interquartile range 4 to 8 days).

Casirivimab + imdevimab reduced viral load in seronegative patients on low-flow or no supplemental oxygen by a least squares mean difference compared with placebo of -0.28 log10 copies/mL (CI: -0.51, -0.05; P=0.0172); differences over placebo started at day 3 and reached significance at day 7. No appreciable virological benefit was noted in seropositive patients. For the clinical outcome of death or progression to mechanical ventilation from day 1 to day 29 in seronegative patients, 19.4% of those receiving met this endpoint, compared to 10.3% receiving casirivimab + imdevimab, resulting in a 47% relative risk reduction (with 95% CI 17.7, 65.8). The benefit was more pronounced with the 2400 mg dose (8.1%; RRR 47%; 95% CI 17.7, 65.8) than with the 8000mg dose (12.2%; RRR 36.9; 95% CI -3.7, 61.6).

What Is the Evidence to Support Use of AmAbs in Patients with Mild COVID-19?

There are two published trials on the use of casirivimab + imdevimab, and sotrovimab, in patients with mild COVID-19.

Casirivimab + Imdevimab

Casirivimab + imdevimab was investigated in a multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of non-hospitalized patients by Weinreich et al.5 The results of the phase 3 study, are presented here.5

Non-hospitalized laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients were originally randomized to receive placebo, casirivimab + imdevimab 2400 mg IV, or casirivimab + imdevimab 8000 mg IV. Based on phase 1 and 2 results that showed these doses of casirivimab + imdevimab had similar clinical efficacy, and that most clinical events occurred in high-risk patients, the trial protocol was amended. Subsequent patients were randomized to placebo, casirivimab + imdevimab 1200 mg IV, or casirivimab + imdevimab 2400 mg IV; they were also required to have at least one risk factor for severe COVID-19 (i.e., age >50, obesity with BMI > 30, cardiovascular disease including hypertension, chronic lung disease including asthma, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease, or immunocompromised state due to medical condition or immunosuppressive medication).

Eligible patients had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, onset of any COVID-19 symptoms within 7 days of randomization, and were 18 years of age or older. Patients with hypoxia (SpO2 < 93% on room air) were excluded from the trial. Patients who were pregnant at randomization were enrolled in the trial, but the results of this cohort have not yet been reported. Patients who were previously vaccinated or infected with COVID-19 were not excluded. The primary endpoint was a composite outcome of all-cause mortality or COVID-19-related hospitalization at 29 days. Key secondary clinical endpoints were: all-cause mortality or a COVID-19-related hospitalization from day 4 through day 29; and COVID-19 symptom resolution.

Patients were enrolled between September 24, 2020 and January 17, 2021 at 115 sites, mostly in the United States. On February 19, 2021 the trial stopped enrolling patients in the placebo arm. In the amended phase III protocol, 2519 patients with at least one risk factor underwent randomization. 2048 patients with at least one risk factor were also included from the original phase III protocol, which randomized patients to 8000 mg or 2400 mg arms.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the usual care and casirivimab + imdevimab groups. The most common risk factor for severe COVID-19 was obesity (58%). Baseline antibody testing revealed 23.6% of patients had baseline SARS-CoV-2 antibodies (seropositive), and 68.6% were antibody negative (seronegative), with 7.8% missing antibody data. Baseline antibody testing was not used to determine treatment allocation.

In terms of the primary clinical endpoint, both casirivimab + imdevimab 2400 mg and 1200 mg significantly reduced COVID-19-related hospitalization or all-cause death compared to placebo (71.3% relative risk reduction [1.3% vs 4.6%; p<0.0001] and 70.4% relative reduction [1.0% vs 3.2%; p=0.0024], respectively). Comparable relative risk reductions were achieved by both baseline seronegative and baseline seropositive patients compared to placebo. Similarly, there were comparable relative risk reductions in both the 2400 mg and 1200 mg arms. There was no significant harm signal, including infusion-related adverse events.

Symptom resolution occurred 4 days earlier in both treatment dose groups than in the placebo groups (10 days vs 14 days, respectively; p<0.0001, 2400 mg and 1200 mg). Those treated with casirivimab + imdevimab who were hospitalized had non-statistically significant shorter stays (2400 mg, median 6.0 vs 7.0 days, n=80; 1200 mg, 4.0 vs 5.5 days, n=31) and were less likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) than those treated with placebo who were hospitalized (2400 mg, 0.4% vs 1.3%, relative risk reduction 67% [95% CI 17.2-86.9]; 1200mg, 0.4% vs 0.9%, relative risk reduction 56.4% [95% CI 67.8-88.7]).

Due to the time window of enrollment, it is likely that most enrolled patients in the trial were not infected with the Delta variant.

Sotrovimab

Sotrovimab was investigated in a multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of non-hospitalized patients by Gupta et al.6 The results of the phase 3 study, currently published as a preprint, are presented here.

Non-hospitalized symptomatic COVID-19 patients were randomized to an IV infusion of sotrovimab 500 mg or placebo (n = 583). They were also required to have at least one risk factor for disease progression (i.e., age ≥ 55, obesity with BMI > 30, diabetes mellitus, congestive heart failure New York Heart Association class > 1, chronic kidney disease GFR < 60 mL/min, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or moderate to severe asthma).

Eligible patients had laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 (positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or antigen testing), onset of any COVID-19 symptoms within 5 days of randomization, and were 18 years of age or older. Patients were excluded if they had respiratory distress, dyspnea at rest, or requiring supplemental oxygen. Patients who were pregnant or breastfeeding, severely immunocompromised, and those who received a COVID-19 vaccine at any point prior to enrollment were excluded. Patients who had prior infection were not excluded. The primary efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients with COVID-19 progression, defined as hospitalization longer than 24 hours, or death, through day 29.

Patients were enrolled between August 27, 2020 and January 19, 2021 at 37 sites in the United States, Canada, Brazil, and Spain. Baseline characteristics were similar between the usual care and the sotrovimab groups. The most common risk factors were obesity (63%), age 55 years or older (47%), and diabetes requiring medication (23%). Baseline antibody testing was not reported.

In terms of the primary clinical endpoint, the risk of COVID-19 progression was significantly reduced in the sotrovimab arm (85% relative risk reduction [1% vs 7%], 97.24% CI 44-96, p = 0.002); the CI was adjusted for the interim analysis. There was no significant harm signal, including infusion-related adverse events. Due to the time window of enrollment, it is likely that most enrolled patients were not infected with the Delta variant.

What Is the Evidence to Support Use of AmAbs in Post-exposure Prophylaxis Settings?

There are two studies that have explored post-exposure prophylaxis in contacts of persons with COVID-19.

The first study, BLAZE-2,7 was a multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of residents and staff in long-term care and assisted living facilities in the United States by Cohen et al. The results of the peer-reviewed phase 3 trial are presented here.

Uninfected residents (n = 300) and staff (n = 666) at a facility with at least 1 confirmed SARS-CoV-2 case were randomized to bamlanivimab 4200 mg or placebo. Eligible subjects had to have negative PCR testing and serology. The primary efficacy endpoint was symptomatic PCR-positive COVID-19 within 8 weeks of randomization.

Patients were enrolled between August 2 and November 20, 2020 at 74 facilities in the United States. Baseline characteristics were similar between the bamlanivimab and placebo arms. In terms of the primary endpoint, the incidence of symptomatic COVID-19 progression was significantly reduced in the bamlanivimab arm (43% reduction [8.5% vs 15.2%], 95% CI 28-68, p < 0.001). There was no significant harm signal, including infusion-related adverse events. Due to the time window of enrollment, subjects were unvaccinated and not exposed to the Delta variant.

As mentioned above, bamlanivimab is authorized by Interim Order through Health Canada. However, it is now accepted that bamlanivimab monotherapy possesses insufficient neutralizing activity against the Delta variant.8 Bamlanivimab in combination with etesemivab, and etesemivab alone, may retain sufficient neutralizing activity against the Delta variant, but etesemivab is currently not approved by Health Canada; furthermore, it appears that bamlanivimab in combination with etesevimab has reduced neutralization activity against the Beta, Gamma, and “Delta plus” (AY.1/AY.2) variants.9,10

The second trial was a multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of previously uninfected household contacts of infected persons (Part A) and recently infected asymptomatic persons (Part B) by O’Brien et al.4The results of the peer-reviewed phase 3 study of Part A are presented here.

Uninfected participants 12 years of age or older were enrolled within 96 hours after a household contact was diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection to receive casirivimab + imdevimab 1200 mg subcutaneously or placebo (n=1505). Subjects were required to be RT-qPCR negative for SARS-CoV-2 and previously uninfected, but the primary efficacy analysis consisted of patients who were also seronegative at baseline. The primary efficacy endpoint was symptomatic RT-qPCR positive for SARS-CoV-2 within 28 days of randomization.

Patients were enrolled until January 28, 2021 at 112 sites in the United States, Romania, and Moldova. Baseline characteristics were similar between the casirivimab + imdevimab and placebo arms. In terms of the primary endpoint, the incidence of symptomatic COVID-19 progression was significantly reduced in the bamlanivimab arm (81% relative risk reduction [1.5% vs 7.8%], p < 0.001). There was no significant harm signal, although 4.2% of subjects receiving casirivimab + imdevimab experienced an injection-site reaction compared to 1.5% receiving placebo. Due to the time window of enrollment, subjects were not exposed to the Delta variant.

What Clinical Recommendations Has the CPG WG Made around the Use of AmAbs in Symptomatic COVID-19?

Moderately/Critically Ill Patients

Recommendation 1. Unstable patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination

The monoclonal antibody cocktail casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 2400 mg IV is recommended for moderately/critically ill patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, who are within 9 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom, and have demonstrated rapid clinical deterioration. Anti-spike antibody testing is not required.

Recommendation 2. Stable patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, seronegative

The monoclonal antibody cocktail casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 2400 mg IV may be considered for moderately/critically ill patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, who are within 9 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom, and are not clinically at risk of acute decompensation, if SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike antibody testing demonstrates they are seronegative.

Recommendation 3. Stable patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, seropositive

The monoclonal antibody cocktail casirivimab + imdevimab is not recommended for moderately/critically ill patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, who are within 9 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom, and are not clinically at risk of acute decompensation, if SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike antibody testing demonstrates they are seropositive.

Recommendation 4. Patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule ofvaccination, seronegative

The monoclonal antibody cocktail casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 2400 mg IV may be considered for moderately/critically ill patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, who are within 9 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom, if SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike antibody testing demonstrates they are seronegative.

Recommendation 5. Patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, seropositive

The monoclonal antibody cocktail casirivimab + imdevimab is not recommended for moderately/critically ill patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, who are within 9 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom, if SARS-CoV-2 anti-spike antibody testing demonstrates they are seropositive.

Recommendation 6. Patients beyond 9 days of onset of COVID-19 symptoms

The monoclonal antibody cocktail casirivimab + imdevimab is not recommended for moderately/critically ill patients who are beyond 9 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom, whether or not they are presumed to have immunity through previous infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination.

Mildly Ill Patients

aRisk factors: age >50 years, indigenous (First Nations, Inuit, or Metis), obesity, cardiovascular disease (including hypertension), chronic lung disease (including asthma), chronic metabolic disease (including diabetes), chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, immunosuppressionb, or receipt of immunosuppressantsb

bExamples include: active treatment for solid tumor and hematologic malignancies, receipt of solid-organ transplant and taking immunosuppressive therapy, receipt of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cell or hematopoietic stem cell transplant (within 2 years of transplantation or taking immunosuppression therapy), moderate or severe primary immunodeficiency (e.g., DiGeorge syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome), resident of long-term care, advanced or untreated HIV infection, active treatment with high-dose corticosteroids (i.e., ≥20 mg prednisone or equivalent per day when administered for ≥2 weeks), alkylating agents, antimetabolites, transplant-related immunosuppressive drugs, cancer chemotherapeutic agents classified as severely immunosuppressive, tumor-necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, and other biologic agents that are immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory. These individuals should have a reasonable expectation for 1-year survival prior to getting infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Recommendation 7. Patients with no history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule ofvaccination, with risk factors

The monoclonal antibody cocktail casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 1200 mg IV or SC OR sotrovimab at a dose of 500 mg IV is recommended for mildly ill patients who meet the following criteria:

- No history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, AND

- Confirmed, symptomatic COVID-19, AND

- Within 7 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom, AND

- At least one of the following risk factors: age > 50, indigenous (First Nations, Inuit, or Metis),11,12 obesity, cardiovascular disease (including hypertension), chronic lung disease (including asthma), chronic metabolic disease (including diabetes), chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, immunosuppression, or receipt of immunosuppressants).13

- Anti-spike antibody testing is not required

Recommendation 8. Patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule ofvaccination, immunocompromised or immunosuppressed

The monoclonal antibody cocktail casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 1200 mg IV or SC OR sotrovimab at a dose of 500 mg IV may be considered for mildly ill patients who meet the following criteria:

- History of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination, AND

- Confirmed symptomatic COVID-19 AND within 7 days of onset of any COVID-19 symptom, AND

- Immunocompromised or immunosuppressed

- Anti-spike antibody testing is not required

Examples of immunocompromised or immunosuppressed individuals include individuals with active treatment for solid tumor and hematologic malignancies, receipt of solid-organ transplant and taking immunosuppressive therapy, receipt of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cell or hematopoietic stem cell transplant (within 2 years of transplantation or taking immunosuppression therapy), moderate or severe primary immunodeficiency (e.g., DiGeorge syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome), resident of long-term care,14 advanced or untreated HIV infection, active treatment with high-dose corticosteroids (i.e., ≥ 20 mg prednisone or equivalent per day when administered for ≥ 2 weeks), alkylating agents, antimetabolites, transplant-related immunosuppressive drugs, cancer chemotherapeutic agents classified as severely immunosuppressive, tumor-necrosis factor (TNF) blockers, and other biologic agents that are immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory. For individuals who are immunosuppressed or receiving immunosuppressants, their condition is considered both an underlying risk factor AND a marker of insufficient ability to mount an immune response to SARS-CoV-2. These individuals should have a reasonable expectation for 1-year survival prior to getting infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Those with no history of infection or having received a full recommended schedule of vaccination are covered under non-immune to SARS-CoV-2.

Recommendation 9. Patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule ofvaccination, with risk factors other than immunocompromise or immunosuppression

Monoclonal antibody therapy is not recommended for all other patients with presumed immunity (through receiving a full recommended schedule of vaccination or previous infection).

Recommendation 10. Patients with a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection or having received a full recommended schedule ofvaccination, with no risk factors

Monoclonal antibody therapy is not recommended for patients at low risk of adverse outcomes, whether or not they are presumed to have immunity.

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

Casirivimab + imdevimab at a dose of 1200 mg IV or SC OR sotrovimab at a dose of 500 mg IV is recommended for unvaccinated individuals or individuals not expected to mount an adequate immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination (including the immunosuppressed or immunocompromised as described above). Due to limited supply, and implementation challenges, we recommend that post-exposure prophylaxis should currently be offered only to hospital inpatients, and those residing in congregate settings (e.g., long-term care, retirement homes, shelters, correctional facilities, etc.) who have had a high-risk exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (as determined by an expert in Infection Prevention and Control or Public Health) and who are at high-risk to progress to moderate or severe COVID-19. Determination of using an AmAb for PEP should take into account the nature and context of their exposure.

Distribution of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Monoclonal Antibody Therapy to Non-hospitalized Individuals

It is recommended that anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibody therapy be administered to non-hospitalized individuals across Ontario using a hybrid network that includes, but is not limited to, MIH services, CP, and outpatient infusion clinics. Administering AmAbs to non-hospitalized individuals requires substantial health care system coordination. Experience from other jurisdictions suggests that a combination of MIH services, CP and infusion clinic-based therapy offer the highest probability of delivering AmAbs to those likely to benefit in a timely manner, preventing unnecessary illness and healthcare utilization.

Are There Special Considerations with Pregnancy and Lactation?

There are currently limited high-quality data on the use of casirivimab + imdevimab and sotrovimab in COVID-19 patients who are pregnant or lactating – a situation which applies to the overall management of COVID-19 in these individuals. However, given the mechanism of action of AmAbs, and the well-established safety profile of products like IV immunoglobulin and plasma in individuals who are pregnant or lactating, these agents are presumed to be safe. They should be used if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk – as they would in any patient. Compared with non-pregnant reproductive-aged peers diagnosed with COVID-19, the relative rates of hospitalization and admission to ICU were significantly increased (RR 4.26 95% CI 3.45-5.10 – hospitalization; RR 11.39 95% CI 7.90-15.21 0 ICU admission).15The Working Group reinforced that principles of COVID-19 management that apply to non-pregnant, non-lactating patients should be equitably applied to pregnant or lactating patients as well. Pregnant patients with COVID-19 should ideally be cared for by multidisciplinary teams familiar with the management of pregnancy.

What Factors Must Be Considered to Promote Ethical, Equitable Allocation of AmAbs?

There is strong mechanistic and clinical evidence supporting the use of monoclonal antibodies early in SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially in those who do not have pre-existing antibodies (i.e., seronegative patients). There are clear barriers to allocating drugs and biologics ethically and equitably, however strategies can be put in place to address these barriers.

During periods of drug scarcity, drug doses are an important consideration. The trial by Somersan-Karakaya et al supports the use of a lower dose of casirivimab + imdevimab (2400 mg) than was used in the RECOVERY trial for seronegative patients admitted to hospital with severe COVID-19.2,3 Although the lower dose of casirivimab + imdevimab was not used in more severely ill patients, we believe that use of the lower dose in more severely ill seronegative patients is reasonable as they are expected to have a lower viral load.

The implementation and availability of baseline antibody testing are also important considerations, to ensure that AmAbs are given to patients most likely to benefit. Laboratory infrastructure is required to provide timely baseline anti-spike antibody testing results. There are a variety of different SARS-CoV-2 serological assays available at present. Assays that do not test for anti-spike protein antibodies (e.g., that test for anti-nucleocapsid antibodies) are not appropriate to determine seronegativity, as they will miss protection conferred by COVID-19 immunization.

Patients admitted to hospital require baseline antibody testing to confirm their serostatus if they are stable. However, these hospitalized patients are logistically easier to test - and no new infrastructure is required to administer an IV infusion, if they are eligible for AmAbs. Conversely, evidence supports foregoing baseline anti-spike antibody testing in outpatients eligible for casirivimab + imdevimab, and the required dose is lower (thus less costly and more resource-conserving). Yet, the implementation barriers in outpatients and congregate care are more significant. These barriers become more manageable if the route of administration shifts from IV infusion to SC administration. Pharmacokinetic data, virology data, and indirect evidence from a trial of casirivimab + imdevimab in asymptomatic patients with early SARS-CoV-2 infection suggest that SC administration of casirivimab + imdevimab is a reasonable alternative to IV administration; this could make it more straightforward for casirivimab + imdevimab to be given by a variety of healthcare providers in a variety of settings, maximizing the therapeutic benefit of this agent for treatment of COVID-19. It is, however, important to note that the required post-administration monitoring period of at least 60 minutes is unchanged between SC and IV dosing).4

The median time to reach maximum serum concentration (Cmax) following a single SC 1200 mg dose of casirivimab + imdevimab is 7 - 8 days. The observed serum concentrations 1 hour after SC infusion is roughly 27% that of IV infusion. Serum concentrations 28 days after a single 1200 mg IV or SC dose are comparable.16 The Working Group acknowledges that the SC use of casirivimab + imdevimab for COVID-19 treatment is based on indirect data from the SC use of casirivimab + imdevimab for post-exposure prophylaxis.4 The Group believes this extrapolation of data is justified as casirivimab + imdevimab is rapidly absorbed when administered subcutaneously, the mean concentration of each antibody component (casarivimab, imdevimab) in serum the day after administration is 22.1 and 25.8 mg/L, respectively, and concentrations continue to rise after day 1 through day 7 post-administration. The neutralization dose for casirivimab + imdevimab is approximately 20 mg/L and does not substantially differ for the Alpha and Delta variants, and the "wild type" SARS-CoV-2.8,16

Based on current clinical evidence, there are three approaches for using AmAbs that will reduce hospital ward and ICU bed use. These three approaches are: 1) treating moderately/critically ill hospitalized, seronegative patients; 2) treating mildly ill high-risk symptomatic outpatients; and 3) post-exposure prophylaxis in high-risk patients who have had high-risk exposures. The number of outpatients needed to treat to prevent one hospitalization based on clinical trial data ranges from 17 to 30. Similarly, the number of hospitalized patients needing to be treated to prevent one ICU admission is 25, and to prevent one death is 18, based on clinical trial data.

The Working Group appreciates that the decisions to treat these three populations are not mutually exclusive; treating outpatients will likely reduce the need to treat hospitalized patients. Additionally, recent data from CIHI shows that patients who would be eligible for outpatient therapy,17 when hospitalized, have a length of stay of 20 days, compared with 11 days for those without comorbidities; they also were more likely to require ICU admission (28% vs 18%). Treating outpatients may well reduce community spread (including spread to vulnerable community-dwelling individuals who are unvaccinated, or who cannot mount a robust immune response), while treating hospitalized patients may reduce nosocomial spread (including spread to vulnerable hospitalized patients and to healthcare providers). Any treatment decision will have an impact on health and human resource needs in Ontario.

There are important ethical issues inherent in the implementation of anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibody treatment. Based on historic patterns of infection and current immunization rates, the spread of severe COVID-19 during the current and future waves may differ from prior waves, disproportionately impacting communities with low immunization rates. This includes rural and remote communities that cannot easily access tertiary hospital care. Any implementation of AmAbs must account for structural urbanism, a bias in health care towards large population centers due to:18

- a market orientation in health care which necessitates a critical mass of customers to make services viable;

- a public health focus on changing outcomes at the population level, which differentially allocates funding toward large population centers;

- and the innate inefficiencies of low-population and remote settings, in which even equal funding will not translate into equitable funding.

The risk of structural urbanism may be profound in treatment with monoclonal antibodies, especially for outpatients who require timely diagnosis and then timely access to antibody administration.

How Can We Optimize the Distribution, Supply, and Administration of AmAbs to Maximize Benefit?

At the time of publication, Ontario is experiencing a wave of SARS-CoV-2 infections due to the Delta variant. Patients at highest risk of poor outcomes are those who are unvaccinated or immunocompromised. AmAbs have been shown to save lives, prevent hospitalization, and reduce ICU admission in eligible patients. However, the demand from potentially eligible patients may exceed supply in the coming weeks based on projected cases, hospitalizations, and ICU admissions.19

Ontario’s at-risk population will consist of those who are unvaccinated, and those who fail to mount an effective immune response to vaccination (either from immunosuppression or waning immunity). It is unlikely that policies related to monoclonal antibody eligibility (i.e., widespread availability) will substantially influence vaccine uptake among those currently unvaccinated. Should unvaccinated individuals become infected, they will remain at substantial risk of severe illness, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19. The Working Group emphasized that treatment should not be withheld from eligible patients (in accordance with direction provided herein) solely for punitive reasons (i.e., because these individuals chose not to be vaccinated) or solely for coercive reasons (i.e., to compel these individuals to be vaccinated).

These considerations dictate that it is critical to develop a robust conservation and implementation plan for AmAbs in Ontario that ensures eligible patients receive it in an ethical, equitable, evidence-informed fashion.

Operational Considerations

Operational considerations for efficient use include the optimal use of drug vials. Casirivimab + imdevimab is supplied as casirivimab + imdevimab concentrate for infusion, as either two single-use 6 mL vials (each containing 300 mg of one monoclonal antibody) or two single-use 20 mL vials (each containing 1332 mg of one monoclonal antibody) per package. Centers which only have access to 20 mL vials, for example, would risk wasting product by administering a 1200 mg dose to a single patient. Consideration must be given to distributing the vials in a fashion that would minimize wastage.

Use can also be optimized by using SC injection as an alternative route of administration whenever IV administration poses a barrier, is not feasible, and/or would lead to a delay in treatment. An example would include treatment in the ambulatory setting. Clinical monitoring after injection for at least 1 hour is recommended regardless of the route of administration. Implementation of AmAbs, specifically in the outpatient setting, will require creation of accessible, equitable infrastructure with trained staff to administer the drug and supervise patients after infusion. Discussion of this is beyond the scope of this brief, but can include infusion clinics, emergency medical services (including community paramedic programs), and other novel, accessible, equity-focused medication delivery models.

Choice of agent is another strategy that might influence operational considerations. The decision of which AmAb to use should be based on clinical evidence, as well as local/regional factors that include availability, the need for different formulations, and activity against locally circulating variants. Transparent real-time information on the supply chain is essential to support drug distribution.

At the time of publication, press releases have been issued for the efficacy of oral antivirals,20,21 although only molnupiravir is under review for authorization by Health Canada at this time. The Drugs & Biologics Clinical Practice Guidelines Working Group believe that these therapeutics may play an important role in the early management of COVID-19, but won’t obviate the need for monoclonal antibody therapy in the near future. Updates to our therapeutic guidelines will account for any new evidence and authorizations.

Applying a Risk Framework to Patient Selection

AmAbs have been shown to reduce hospitalization, ICU admission, and death in outpatients. These neutralizing antibodies have also been shown to reduce ICU admission and death in inpatients. Due to limited supply, consideration can be given to administering this drug to individuals who are most at risk for poor outcomes from COVID-19, including First Nations, Metis and Inuit peoples.11,12,22,23 The largest study of casirivimab + imdevimab in outpatients (by Weinreich et al.) relies heavily on risk factors to capture eligible patients; the trial’s list of risk factors is very broad, and not all risk factors impact patient outcomes equally.5 The following proposed risk framework for AmAb use in outpatients is based on current published international and Canadian data around highest risk prognostic factors for mortality as an outcome of COVID-19:24–33

Drug Supply Very Restricted

If drug supply is very restricted, use should be restricted to casirivimab + imdevimab for seronegative inpatients moderately or critically ill with COVID-19, and sotrovimab for post-exposure prophylaxis (as outlined previously in this document) and eligible outpatient who are: ≥ 70 years of age AND have at least one additional risk factor; or ≥ 50 years of age AND First Nations, Inuit, or Metis AND have at least one additional risk factor.7,34 Additional risk factors are as follows:

- Obesity (BMI ≥ 30)

- Dialysis, or stage 5 kidney disease (eGFR < 15)

- Diabetes

- Cerebral palsy

- Intellectual disability (of any severity)

- Sickle cell disease

- Receiving active cancer treatment

- Solid organ or stem cell transplant recipients

All patients should have a reasonable expectation for 1-year survival prior to getting infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Drug Supply Expanding

As drug supply expands, use of casirivimab +imdevimab should continue for seronegative patients moderately or critically ill with COVID-19, and whatever AmAb supply is otherwise available should be given to eligible outpatients who: have Down Syndrome and are ≥ 18 years of age;30 or are ≥ 60 years of age AND have at least one additional risk factor; or are ≥ 40 years of age AND First Nations, Inuit, or Metis AND have at least one additional risk factor.34,35Additional risk factors are as follows:

- Obesity (BMI ≥ 30)

- Dialysis, or stage 5 kidney disease (eGFR < 15)

- Diabetes

- Cerebral palsy

- Intellectual disability (of any severity)

- Sickle cell disease

- Receiving active cancer treatment

- Solid organ or stem cell transplant recipients

All patients should have a reasonable expectation for 1-year survival prior to getting infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Drug Supply Further Expanding

If supply expands further, eligible outpatients should include those in the original recommendations cited above (i.e., age ≥ 50, indigenous (First Nations, Inuit, or Metis), obesity, cardiovascular disease (including hypertension), chronic lung disease (including asthma), chronic metabolic disease (including diabetes), chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, immunosuppression, or receipt of immunosuppressants).1 Consideration could be given to other persons at increased risk, including younger adults with cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, sickle cell disease, and pregnant individuals. These individuals should have a reasonable expectation for 1-year survival prior to getting infected with SARS-CoV-2.

The CPG WG acknowledges the limitations of the above risk framework, given the many factors that impact baseline risk with COVID-19 (some of which likely act synergistically), the challenges of establishing the presence of important baseline risk factors (including frailty, and the chance of 1-year survival prior to SARS-CoV-2 infection), and the uncertainty over whether AmAbs have different effects in different clinical subgroups.

Ethics- And Evidence-Based Considerations

An ethical, evidence-based framework is required to inform allocation and use of limited anti-SARS-CoV-2 monoclonal antibody supply. The Ontario COVID-19 Bioethics Table adapted a published Ontario drug supply shortage framework for use during the COVID-19 pandemic.36,37 It outlines a set of guiding ethical principles (Table 1) and three stages for managing drug supply during the COVID-19 pandemic:

Stage 1: Preserve the standard of care for as many COVID-19 patients as possible by conserving supply, sharing supply, and procuring or accessing new supply.

Stage 2: Optimize therapeutic benefit based on existing evidence within available supply (Primary Allocation Principle).

Stage 3: Use a fair procedure to choose between COVID-19 patients (Secondary Allocation Principle) if Stage 1 and 2 efforts are insufficient to meet demand.

| Principle | Description |

| Beneficence | Maintain highest quality of safe and effective care based on available evidence and within available resources (i.e., drug supply) |

| Equity | Ensure fair and non-discriminatory access to resources |

| Reciprocity | Respond to each other in similar ways that recognize mutual interdependence |

| Solidarity | Build, preserve and strengthen inter-professional / -institutional / -sectoral / -provincial collaborations and partnerships |

| Stewardship | Use available resources responsibly (e.g., to optimize therapeutic benefit and sustain available supply) |

| Trust | Foster and maintain public, patient and healthcare provider confidence in health system |

| Utility | Maximize the greatest possible good for the greatest possible number of individuals with available resources |

Guided by these ethical principles, a set of recommendations was developed for allocation of tocilizumab in COVID-19’s 3rd wave. The Working Group believes these recommendations should be adopted to rationally allocate AmAbs at each stage of the Ontario drug supply shortage framework.

Recommendations and Options

If Ontario were to enter an AmAb shortage – which it may already have based on the estimated number of eligible patients, and the known current supply of drug available through the Public Health Agency of Canada – it would need to consider procurement of additional product, and approaches that optimize the effectiveness and equity of the existing supply. Working from the Ontario COVID-19 Bioethics Table framework noted above, this Science Brief provides recommendations and options at each stage.

All Stages of Managing Casirivimab + Imdevimab Supply and Distribution

- Use should follow the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table’s Clinical Practice Guidelines, which are supported by randomized, controlled clinical trials (supported by beneficence). The Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table’s Recommendations account for the best available evidence in identifying COVID-19 patients with proven benefit from casirivimab + imdevimab therapy.

- Casirivimab + imdevimab should be allocated province-wide to optimize therapeutic benefits and ensure equitable access for all eligible COVID-19 patients in Ontario (supported by beneficence, equity, reciprocity, solidarity, and trust). Particular attention should be paid to where populations most likely to benefit are currently located. This would include proactively understanding where the highest concentrations of unvaccinated individuals reside and seek care, and the disease epidemiology in these locations. Centralized or coordinated allocation at the provincial and/or regional need may at least partially mitigate structural urbanism.

- The minimum effective dose of casirivimab + imdevimab should be used in line with the evidence in this brief (supported by beneficence, equity, stewardship, and utility). As mentioned above, there are also pharmacologic and clinical rationales for using SC administration in the outpatient setting. These two strategies would immediately increase supply for eligible Ontario COVID-19 patients.

Options for All Stages of Managing Drug Supply and Distribution

- The assessment of the stage of antibody shortage should be based on predicted demand and communicated clearly to all clinical stakeholders (supported by beneficence, equity, and stewardship). Exponential growth of SARS-CoV-2 and changing public health measures in the community makes it difficult for most people to predict future AmAb needs. This requires mathematical modeling support to estimate the total future needs based on expected supply. If only ICU admissions are available, a reasonable estimate of all hospitalized COVID-19 patients (ICU and non-ICU) can be acquired by increasing this threefold (in the RECOVERY trial, the ratio of patients mechanically ventilated to those non-mechanically ventilated or without ventilatory support was approximately 1:1).38 Using this figure, and similar Ontario-specific information on cases, hospitalizations, and ICU admissions, a projection of demand in subsequent weeks can be made, with re-evaluation (and possibly re-calibration) weekly depending on observed usage.

- Ontario could create a near real-time provincial dashboard accessible to all clinical stakeholders that includes currently available casirivimab + imdevimab supply, and allocated and administered doses (by region, site, and indication). This dashboard could also include any anticipated shipments (supported by beneficence, equity, reciprocity, solidarity, and trust). Having transparent data creates trust and a sense of solidarity, as all participants share with the need to preserve resources. Additionally, it makes it easier to recognize where some regions or sites might have substantially depleted supply, facilitating quicker responsiveness. This principle of a near-real time dashboard was why Ontario’s Critical Care Information System (CCIS) was created: in 2003, Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) highlighted the need to improve Ontario’s critical care system. In 2006, Ontario’s Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (now separated into MOH and MLTC) announced Ontario’s Critical Care Strategy, and CCIS data collection began in 2007. CCIS data has been available throughout the COVID-19 pandemic to support monitoring and managing ICU bed and ventilator capacity.

- There could be a provincially coordinated mechanism building on the Incident Management Systems (IMS) to allow transfer of medication (or, rarely, patients) to ensure that any eligible COVID-19 patient can receive timely, evidence-based therapy (supported by equity and solidarity). Because of the sparse supply and cost of casirivimab + imdevimab and the uneven distribution of COVID-19 patients across the province, patients may present to health care facilities that will not have access to rapid baseline serologic testing and/or casirivimab + imdevimab.

- The optimal turnaround time (TAT) from laboratory receipt for serologic testing is 24 hours, however laboratory resource constraints, transport time, and availability of testing on the weekends in different parts of the province may make it challenging to meet this TAT and ensure clinicians have rapid access to test results on which to base their clinical decisions. Regions are encouraged to establish processes with their referral laboratory (which in some cases, is the Public Health Ontario Laboratory) that optimize pre-analytical factors and set expectations around TAT.

Recommendations for Stage 2 of Casirivimab + Imdevimab Supply and Distribution

- Triaging COVID-19 inpatients for casirivimab + imdevimab therapy based on additional clinical factors deemed to be associated with additional benefit from therapy is not advisable: the data are insufficient to define groups of COVID-19 patients most likely to benefit from treatment. Denying COVID-19 patients with milder illness might increase the number of patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Operationally, this adds challenges that are unlikely to result in a consistent and equitable allocation of casirivimab + imdevimab.

Options for Stage 2 of Casirivimab + Imdevimab Supply and Distribution

- Below, we outline issues around inpatient supply. However, outpatient supply adds an additional complexity – especially recognizing that in the event of a shortage, decisions will need to be made between giving 8000 mg of casirivimab + imdevimab to 1 inpatient vs. 1200 mg to roughly 6 outpatients.

- Distribution of product could be weekly and site-specific, with allocation based on prior week’s consumption (supported by equity, stewardship, and trust). With rapid changes in patient numbers, and potential redistribution of COVID-19 patients using an IMS, a prudent approach to distribution would be weekly distribution of antibodies to regions according to an IMS command structure. The IMS command structure can then distribute further based on local needs and supplies.

- Critical care triage guidelines are applicable to surges that occur in a short period of time, and allocation demands immediate choice. Additionally, ventilators cannot be saved today for use tomorrow. In Ontario, these triage guidelines (i.e., the Ontario Critical Care COVID-19 Command Centre’s Emergency Standard of Care) cannot be applied unilaterally by a hospital and can only be applied at the direction of the IMS (i.e., Ontario’s Critical Care COVID-19 Command Centre). A similar process is not applicable to the case of AmAbs as planning for antibody shortages allows allocation in a manner that has greater equity.

Recommendations for Stage 3 of Managing AmAb Shortages

- Develop a logic-based mechanism to fairly ration casirivimab + imdevimab (supported by beneficence, equity, solidarity, stewardship, trust, and utility). If Stage 1 and 2 efforts are insufficient to meet demand, Ontario will need to proceed to Stage 3, and use a fair procedure to choose between COVID-19 patients of equal need for secondary prioritization of casirivimab + imdevimab.36,39 Stage 3 rationing should not occur on a site-by-site basis but provincially, ideally managed through an IMS.

- AmAbs should be given to COVID-19 patients with a reasonable chance of benefiting from it. Because of casirivimab + imdevimab scarcity, it is defensible not to offer these agents to COVID-19 patients who almost certainly will not benefit. This should be based on consensus among those involved in assessing eligibility for allocation.

- A strictly first-come, first-served approach is not recommended, as it would favour patients presenting to centres with known AmAb supply and would certainly reinforce structural urbanism and other health inequities by benefiting those in urban centres (with existing or ready supply) over rural locations.

- Casirivimab + imdevimab administration should continue to be guided by supporting evidence, and COVID-19 patients who meet the eligibility criteria but do not want active medical treatment or specific treatment with monoclonal antibody therapy should neither be offered it nor entered into an allocation system.

Options for Stage 3 of Casirivimab + Imdevimab Supply and Distribution

- To mitigate potential bias influencing the assessment of COVID-19 patients eligible for casirivimab + imdevimab, a second-opinion or consensus model among those responsible for assessing eligibility should be considered.

- An allocation lottery could be the fair default procedure for choosing among eligible COVID-19 patients where allocation based on maximizing benefits cannot be determined. Allocation lotteries have been successfully used in several North American jurisdictions and acknowledges that the efforts to allocate based on maximizing the benefits of therapy have been exhausted. An added potential benefit of an allocation lottery framework is that it could track outcomes of COVID-19 patients offered or declined access to therapy. This would allow for evaluation of real-world use in Ontario. We have described potential allocation lotteries in previous Briefs.37

Interpretation

There is mechanistic and clinical evidence to support the use of AmAbs in select ambulatory and hospitalized patients with symptomatic COVID-19. Provincial demand for these agents may exceed supply in the near future. A science- and ethics-guided approach designed to maximize the benefits of available supply is recommended.

Core recommendations include a focus on ethics and equity in the use of these agents; optimizing the dose and administration of these agents; adhering to evidence-based use; establishing a provincial dashboard of supply and distribution accessible to all stakeholders; and ongoing modeling to estimate supply-to-demand adequacy.

Methods Used for This Science Brief

We searched PubMed and Google Scholar using the following search terms: “sotrovimab,” “REGEN-COV, “bamlanivimab,” “casirivimab,” and “imdevimab.” In addition, we retrieved reports citing relevant articles through Google Scholar and reviewed references from identified articles for additional studies. The search was last updated on September 29, 2021. Expert perspectives were sought from critical care medicine, medical ethics, internal medicine, and pharmacy in Ontario, and we also contacted experts from the United States (JAJ and EKM) who had designed and/or implemented state-wide drug randomization during the COVID-19 pandemic, to provide us with detailed information on various issues around implementation of weighted and unweighted drug lottery systems.

For therapeutic recommendations, we used the following definitions for COVID-19 disease severity:

Critically / Severely Ill

Patients requiring ventilatory and/or circulatory support, including high-flow nasal oxygen, non-invasive ventilation, invasive mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). These patients are usually managed in an intensive care setting.

Moderately Ill

Patients newly requiring low-flow supplemental oxygen. These patients are usually managed in hospital wards.

Mildly Ill

Patients who do not require new or additional supplemental oxygen from their baseline status, IV fluids, or other physiological support. These patients are usually managed in an ambulatory/outpatient setting.

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

Use of a drug, biologic, or vaccine in individuals who are uninfected and asymptomatic but who are at risk of becoming infected and developing COVID-19 after having been exposed to SARS-CoV-2.