Vaccine-Induced Prothrombotic Immune Thrombocytopenia (VIPIT) Following AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccination

Authors:Menaka Pai, Allan Grill, Noah Ivers, Antonina Maltsev, Katherine J. Miller, Fahad Razak, Michael Schull, Brian Schwartz, Nathan M. Stall, Robert Steiner, Sarah Wilson, Ullanda Niel, Peter Jüni, Andrew M. Morris on behalf of the Drugs & Biologics Clinical Practice Guidelines Working Group and the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table

OUTDATED

This version is outdated. Please see https://doi.org/10.47326/ocsat.2021.02.17.2.0 for the latest version of this Science Brief.

Key Message

This Science Brief provides information for health care professionals about Vaccine-Induced Prothrombotic Immune Thrombocytopenia (VIPIT), a rare adverse event following the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

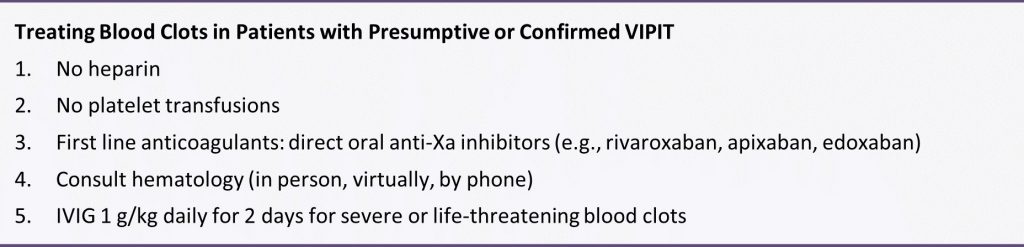

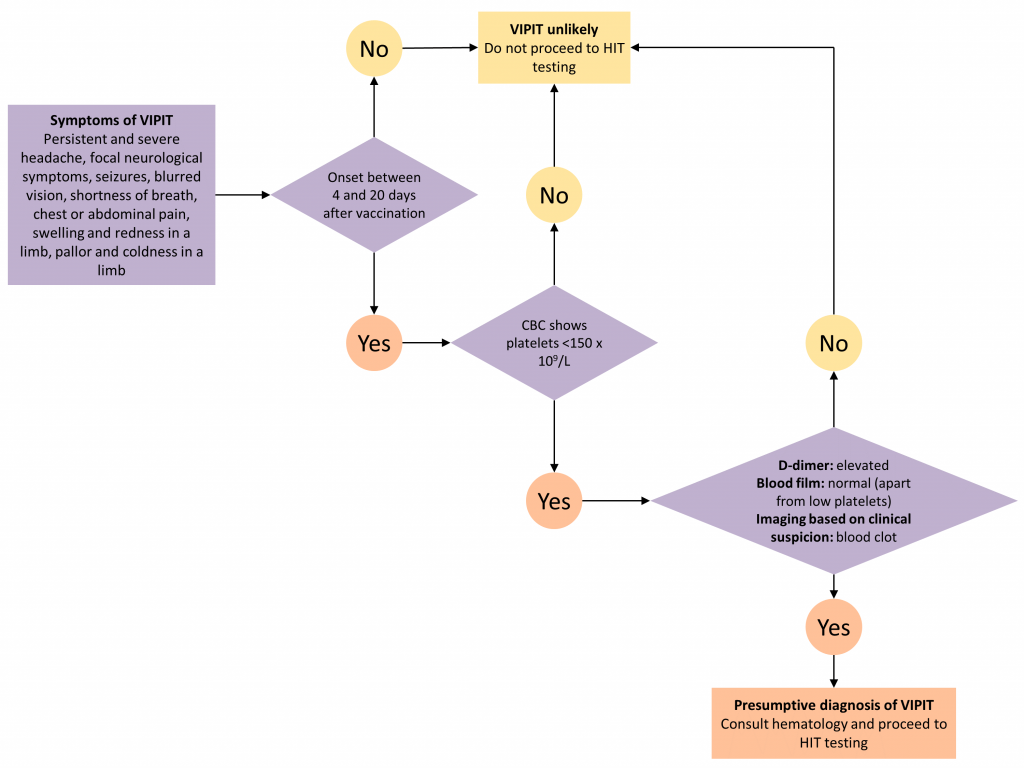

This brief describes the pathophysiology, presentation, diagnostic work-up and treatment of VIPIT. Figure 1 presents a decision tree for diagnosing and ruling out VIPIT.

Lay Summary

What do we know so far?

The United Kingdom, European Union, and Scandinavian countries have reported that the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine appears to be associated with rare cases of serious blood clots, including blood clots in the brain. These blood clots have two important features: they occur 4 to 20 days after vaccination, and they are associated with low platelets (tiny blood cells that help form blood clots to stop bleeding). Doctors are calling this “vaccine-induced prothrombotic immune thrombocytopenia” (VIPIT). VIPIT seems to be rare, occurring in anywhere from 1 in every 125,000 to 1 in 1 million people.

Health Canada has stated that the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine continues to be safe and effective at protecting Canadians against COVID-19 and encourages people to get immunized with any of the COVID-19 vaccines that are authorized in Canada.

Are certain people more likely to get VIPIT?

VIPIT is very rare. At this time, we do not know if certain patients are more likely to get VIPIT. So far, most of the cases from Europe have occurred in women under age 55 – but many of these countries used more of their initial AstraZeneca vaccine supply in women under age 55. We do not believe that VIPIT is more common in people who have had blood clots before, people with a family history of blood clots, people with a low platelets, or pregnant women, because VIPIT does not develop through the same process as usual types of bleeding or clotting problems.

What should you look out for if you received the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine?

You should speak to a health care professional if you have unusual or severe symptoms after any COVID-19 vaccine. If you experience the following symptoms between 4 and 20 days after vaccination, it might indicate that you have VIPIT: a severe headache that does not go away; a seizure; difficulty moving part of your body; new blurry vision that does not go away; difficulty speaking; shortness of breath; chest pain; severe abdominal pain; new severe swelling, pain, or colour change of an arm or a leg. These symptoms can also be a sign of other serious conditions and should be assessed in an emergency department.

What should you do if you have concerning symptoms after the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine?

If your symptoms are not severe, you can see (virtually or in-person) your primary care professional. If you have severe symptoms, you should go to the nearest emergency department immediately. You should tell the health care providers who see you that you received the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine and give them the date you got vaccinated. If the healthcare professional who assesses you is concerned, you may have scans and additional bloodwork collected.

Do healthcare professionals know how to diagnose and treat VIPIT?

Yes. Health care professionals and scientists in Ontario have been working with experts in Canada, and around the world, to better understand VIPIT. The Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table has summarized what we know about VIPIT right now and has published guides for healthcare professionals outside and inside the hospital, to help them diagnose and treat VIPIT.

Why is Ontario still using the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine?

Health Canada reviewed the AstraZeneca COVID-19 Vaccine, as well as a similar vaccine called COVISHIELD. They have stated that the benefits in protecting Canadians from COVID-19 continue to outweigh the risks and encourage Canadians to get immunized with any of the COVID-19 vaccines that are authorized in Canada when they are eligible. Keep in mind that COVID-19 has killed over 15,000 Canadians so far, that about 1 in 100 Canadians who get COVID-19 end up needing intensive care, and that 1 in 5 Canadians who are hospitalized with COVID-19 develop blood clots. Currently Canada is experiencing a third wave of COVID-19. VIPIT is very rare, while the AstraZeneca vaccine has proven effective at reducing severe illness from COVID-19. Health care professionals, scientists, and government agencies in Ontario – and around the world – will continue to monitor the safety of this and all vaccines.

Could other COVID-19 vaccines available in Ontario cause VIPIT?

There have been no confirmed cases of VIPIT with any other COVID-19 vaccine.